The transition from the Sukhothai Kingdom to the Ayutthaya Kingdom in 1351 marked a pivotal shift in Thai history, initiated by King Ramathibodhi I. This era heralded a transformation in the perception of monarchy, deeply influenced by the prevailing Hindu traditions of the Khmer Empire in the region. The ritual of royal coronation was led by Brahmin priests, elevating the king to a divine status, akin to the reincarnation of Hindu deities. The titles adopted by Ayutthaya's rulers reflected this blend of religious and royal imagery, with variations including Indra, Shiva, Vishnu, and notably, Rama, with "Ramathibodhi" illustrating the preference for the latter. Despite the strong Hindu influence, Buddhism's imprint was unmistakable, with kings often referred to as "Dhammaraja," a term derived from "Dharmaraja," symbolizing a ruler guided by Dharma.

In this melting pot of religious and cultural influences, a syncretic model of kingship emerged, reinvigorating ancient practices. Among these, the Devaraja (divine king) concept stood out, tracing its origins to the Hindu-Buddhist traditions of Java and adopted by the Khmer. This model positioned the king as an avatar of Vishnu and a Bodhisattva, grounding his legitimacy in his spiritual authority, moral leadership, and noble lineage. This intricate blend of Hindu and Buddhist elements defined the royal ideology of Ayutthaya, illustrating a complex tapestry of Southeast Asian religious and cultural interactions.

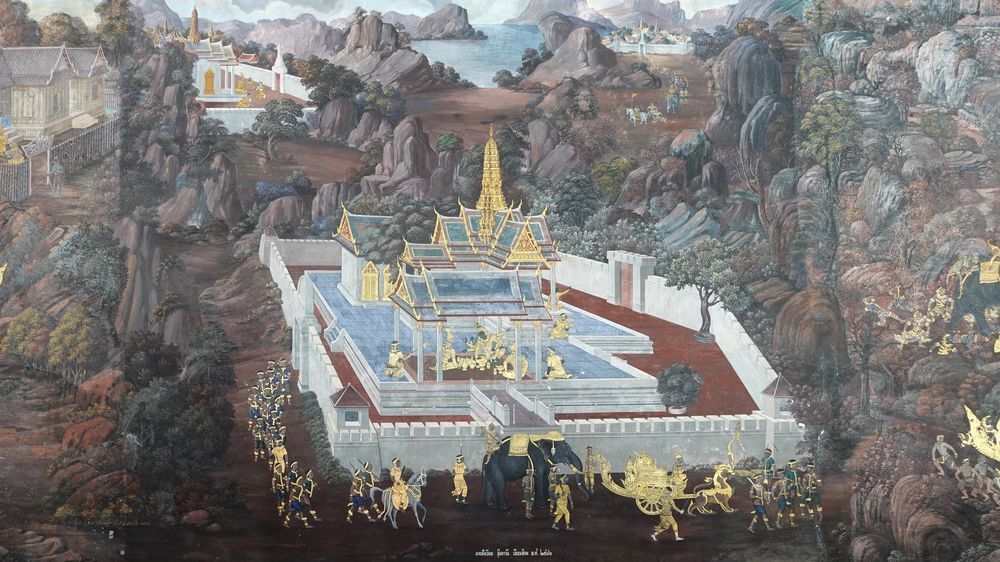

The monarchy, as shaped by the interests of the state, was elevated to a status nearing divinity, transforming the king into an entity deeply revered and worshipped by his subjects. This transformation was a deliberate cultural strategy that distanced the monarchy from the populace, establishing an era of unchecked monarchical power. The royal abodes, inspired by Mount Meru—considered the dwelling of deities in Hindu belief—reflected their divine aspirations. Adopting the title of "Chakravartin," the kings of this era asserted their supreme authority, positioning themselves as the pivotal force around which the universe orbits. Their reign, marked by grand ceremonies and rituals, underscored their omnipotence. For 400 years, these monarchs governed the kingdom of Ayutthaya, overseeing a golden age characterized by remarkable advancements in culture, economy, and military prowess, making it a highlight in the annals of Thai history.

The monarchs of Ayutthaya established numerous frameworks and organizations to bolster their governance. While Europe was navigating the complexities of feudalism during the Middle Ages, in the 15th century, Ayutthaya under King Trailokanat adopted a distinct system known as sakdina. This was a structured social order that classified individuals based on the land they could claim, directly correlating to their societal status and role. Additionally, the kingdom emphasized a unique linguistic tradition, Rachasap, which was a set of honorific terms and a specialized lexicon dedicated to communicating about or directly addressing the royal family, underscoring the cultural importance of respecting hierarchy and royalty in Ayutthaya.

The monarch served as the paramount authority in administration, legislation, and judiciary, essentially embodying the source of all legal decrees, judgments, and sanctions. This supreme power was encapsulated in titles such as "Lord of the Land" and "Lord of Life," underscoring the king's ultimate dominion and control. To outsiders, these roles and honorifics underscored the perception of the monarch as an unequivocal autocrat, akin to the absolute rulers found in Europe. However, within the Siamese framework, the concept of kingship was deeply influenced by ancient Indian principles of governance, aligning more closely with the idea of Enlightened Absolutism. Unlike its Western counterpart which prioritized logic and reason, the Siamese approach placed a greater emphasis on Dhamma, or moral law. This system faced a significant setback in 1767, a tumultuous period marked by the invasion of Ayutthaya by forces from the Alaungpaya Dynasty of Burma. The attack led to the devastating loss of Thai legal texts on the dhammasāt, erasing centuries of accumulated wisdom and tradition.